How to Exercise for Better Cancer Protection

Cancer Prevention Series Part 3: Exercise

What better way to start the new year than with our final post on cancer prevention?

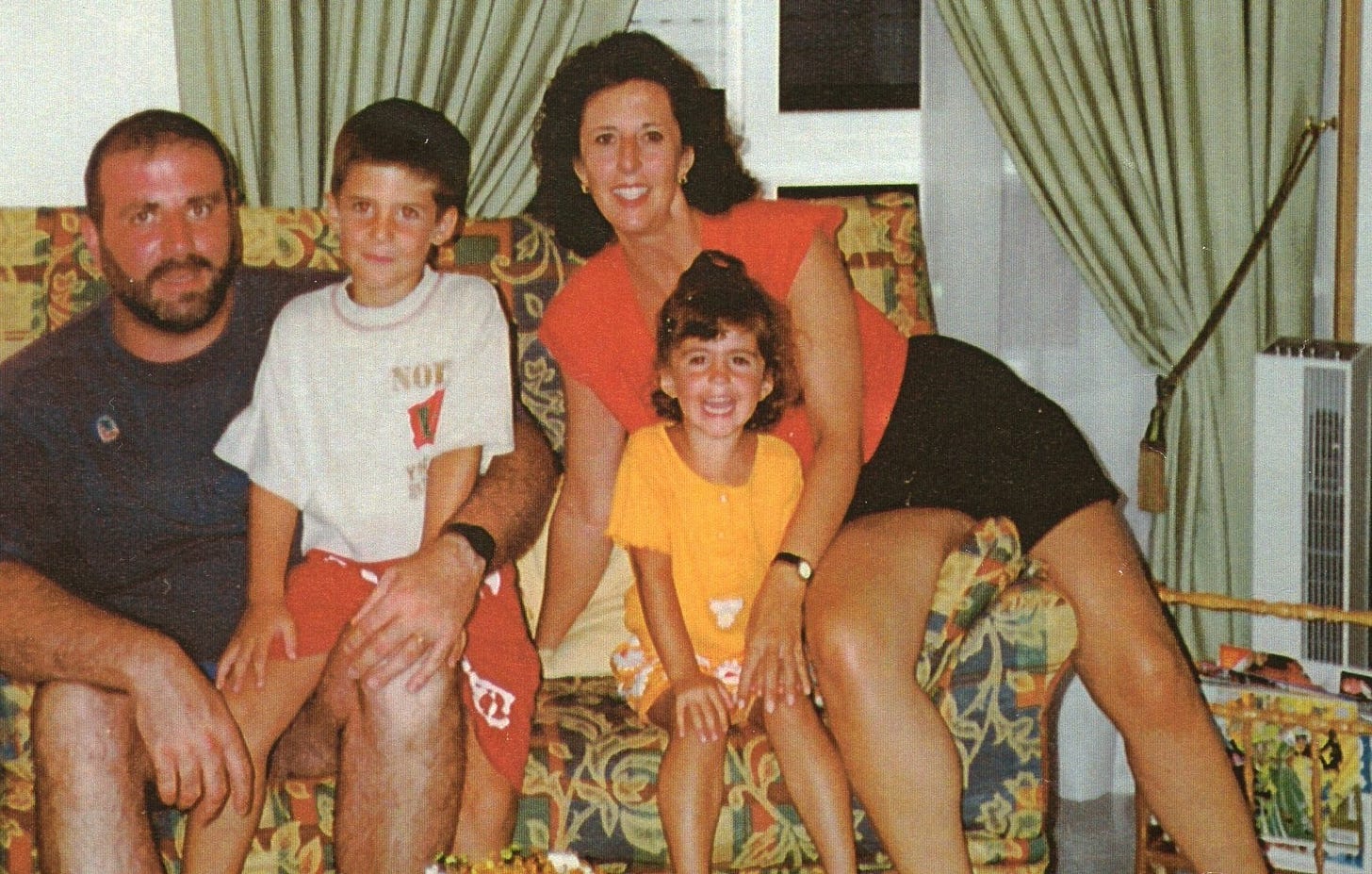

Christmas is a time for family, gifts, community, and gratitude.

When I think of those words, I think of my mother. I also think of you, and of every person who reads these emails hoping to live a longer, healthier life.

In honor of my mom and as a heartfelt thank you to this community, I’m creating something I wish she — and we — had had earlier:

🎁 A completely free series on cancer prevention.

Why This Series Matters So Much

Cancer accounts for one in eight deaths worldwide.

After years of being the second leading cause of mortality, it has already become the number one cause of death in several regions, and by the end of this century, it is estimated to be the leading cause of death in all countries.

About 1 in 5 men and 1 in 6 women will develop cancer at some point in their lives, and 1 in 8 men and 1 in 11 women will die from it.

The most common types of cancer vary by gender:

In women: breast, lung, and colorectal cancer

In men: lung, prostate, and colorectal cancer

Here’s the part that changes everything:

More than 90% of cancers are attributed to modifiable risk factors such as smoking, being overweight, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, and an inadequate diet.

Yet one of the most persistent myths about cancer is that “it’s mostly genetic.” While genes do play a role, for most people they explain only a small fraction of overall cancer risk.

The largest share comes from what we’re exposed to and what we do, day after day — the habits, environments, and choices we can gradually influence.

I wrote about some of the most common health myths debunked by science in this previous post, and I strongly encourage you to read it so you don’t waste time, money, or emotional energy on misinformation.

Confession time: I used to believe some of them too.

Today, I want to focus on what serious, evidence-based organizations actually agree on about prevention — and how you can start applying it in real life.

Why I’m Doing This

As a doctor, patient, and daughter, I have seen cancer from every angle.

My mother was diagnosed with lung cancer despite never having smoked. She underwent chemotherapy, but it was ineffective. She died one year later, while I was in medical school.

Around that time, I learned about another doctor with metastatic ovarian cancer, whose prognosis was similarly poor. But alongside her oncology treatment, she embraced an integrative approach — exercise, nutrition, psychological support, and complementary therapies. Not only did she recover, but she later had children.

It shook me.

Why did my mother never receive this kind of integrative support?

Why was the system almost entirely focused on treating disease, and so little on preventing it and supporting the whole person?

Later, I struggled too — with depression, insomnia, and anxiety — and again, the only solution offered was an antidepressant. No therapy, no support, just a prescription.

These experiences are the reason I do what I do.

They’re the reason I built Zenith Within. From the bottom of my heart, I truly hope this series helps you protect yourself and the people you love.

First Week’s Focus: What All the Major Guidelines Agree On

Last Week’s Focus: Foods and Diets That Fight Cancer

This Week’s Focus: Cancer and Exercise

This week, I’m honored to explore the powerful link between cancer and exercise with Daniel Flora, MD, a medical oncologist who brings equal parts science and humanity to modern cancer care—and whose perspective is deeply personal. He also lost his mother to cancer.

We both agree on something important: treatments have improved dramatically. But too often, they arrive after the disease has already taken hold.

That’s why prevention deserves the same spotlight as treatment.

Thank you, Daniel Flora, MD, for bringing both rigorous science and deep compassion to this conversation.

Why Exercise Is a Key Part of Cancer Prevention

Cancer does NOT develop in isolation. It grows within an internal environment shaped by inflammation, metabolism, hormones, and immune function.

Physical activity influences all of these systems together.

Regular exercise:

Lowers chronic low-grade inflammation

Improves immune surveillance

Enhances insulin sensitivity

Reduces prolonged exposure to growth-promoting hormones such as insulin, estrogen, and insulin-like growth factors

These pathways are particularly relevant for breast, colorectal, endometrial, and prostate cancers.

Many of these benefits occur even when weight does not change. This is why prevention conversations tend to go better when we focus on metabolic health, muscle, and function rather than the number on the scale.

Large studies and meta-analyses consistently show that people who are regularly physically active have a meaningfully lower risk of developing several common cancers, especially breast and colon cancer.

The strongest signal shows up with moderate, steady activity, it doesn’t need to be extreme.

Exercise Prescriptions

Any movement is better than none, but aiming for about 150 minutes per week of moderate activity is a practical goal. That works out to roughly 20 to 25 minutes on most days.

Zone 2 exercise is often recommended. It’s a pace where heart rate is elevated, but a conversation is still possible. You should feel like you are working, but not struggling.

Examples include:

Brisk walking

Steady cycling

Swimming at a comfortable pace

Using an elliptical or rowing machine

For many people, the simplest starting point is a 20 to 30 minute walk after dinner. It requires no equipment and fits naturally into daily life.

A realistic week might look like this:

Monday: 25 minute brisk walk

Tuesday: 25 minute brisk walk

Thursday: 30 minute bike ride or rowing machine

Saturday: 30 minute walk or hike

Resistance training is also an important part of cancer prevention.

Muscle is metabolically active tissue. Maintaining it supports insulin sensitivity, hormonal balance, bone health, and long-term physical function.

Strength training once or twice per week is enough to make a difference. These sessions do not need to be long, 20 to 30 minutes is plenty.

A simple session might include:

Getting up and down from a chair

Push-ups against a wall or counter

Some kind of pulling movement using bands or light weights, step-ups, and a bit of core work.

Machines and free weights work just as well for people who prefer a gym. The goal is not lifting heavy or training to exhaustion. It is keeping muscle as we age.

For those starting from a sedentary baseline, begin with walking and add strength training later once the habit feels solid.

Common Barriers

“I don’t have time”

This is the most common issue. When it comes up, it’s better to shift the goal away from formal workouts and toward movement opportunities. Three 10-minute walks spread across the day still count. Walking during phone calls or adding a short walk after dinner often works better than trying to protect a perfect time slot.

“I’m too tired”

Fatigue often improves with movement rather than rest alone. On low-energy days, lower the bar instead of skipping entirely. A slow walk or gentle movement is often enough to keep the habit alive.

“I have joint pain or old injuries”

Pain changes the plan, not the goal. Walking can be swapped for cycling, swimming, or an elliptical. Strength work can be modified with lighter loads or bands. Avoiding all movement usually makes pain worse over time.

“I’ve never lifted weights and I’m worried about getting hurt”

Strength training does not require heavy weights or complex movements. Bodyweight exercises, bands, and machines are all reasonable places to start. Comfort and confidence matter more than intensity.

“I start strong and then fall off”

This happens to almost everyone. When it does, reset rather than quit. Life interrupts routines. Restarting at a lower level is not failure. It is part of how habits actually form.

“If I can’t do it perfectly, it’s not worth doing”

Exercise does not work in an all-or-nothing way. Short sessions still matter. Partial weeks still count. The body responds to what you do consistently, not what you do perfectly.

Exercise as Part of a Bigger Picture

Exercise works best alongside decent sleep, supportive nutrition, and limited alcohol intake.

Poor sleep worsens insulin resistance and inflammation.

Nutrition affects energy, muscle maintenance, and consistency.

Alcohol increases cancer risk and interferes with recovery.

These pieces tend to reinforce each other. When people start moving more, sleep often improves. When sleep improves, exercise becomes easier to sustain.

The Basics

If all of this feels like a lot, stop there and just focus on a few basics.

Walk most days.

Nothing fancy. 20 or 30 minutes is plenty. Walk fast enough that you feel it, but not so fast that you dread it. If all you ever do is walk after dinner most nights, that alone moves the needle.

Do some kind of strength work once or twice a week.

You do not need a gym or a complicated plan. Getting up and down from a chair, push-ups against a wall or counter, some light pulling with bands or weights, and a little core work is enough. The goal is simply to keep muscle as you age.

Sit less during the day.

Long stretches of sitting seem to matter more than we used to think. Standing up, walking around, or stretching every so often helps. You do not need to track it. Just move a little more than you did yesterday.

If you do those three things most weeks, you are already doing something meaningful for cancer prevention.

Exercise does not eliminate cancer risk. Genetics, diet, and environmental exposures remain part of the equation. But among the things we can influence, physical activity remains one of the most reliable ways we know to shape the biology that drives cancer development over time.

Exercise & Cancer: A Practical Action Guide

📩 You can download the free printable Exercise & Cancer Action Guide here.

I truly hope you found this post, and this series, helpful.

To your zenith within,

Sara Redondo, MD

Daniel Flora, MD

References:

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today [internet]. 2022. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/en.

GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388(10053):1459-1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1.

GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018 Nov 10;392(10159):1736-88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7.

Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016 Nov 7;37(42):3232-3245. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334.

Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee, Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2021 [internet]. 2021. Available from: https://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2021-EN.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today [internet]. 2022. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheet.pdf.

Islami F, Goding Sauer A, Miller KD, Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Jacobs EJ, et al. Proportion and number of cancer cases and deaths attributable to potentially modifiable risk factors in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Jan;68(1):31-54. doi: 10.3322/caac.21440.

Brown KF, Rumgay H, Dunlop C, Ryan M, Quartly F, Cox A, et al. The fraction of cancer attributable to modifiable risk factors in England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 2015. Br J Cancer. 2018 Apr;118(8):1130-1141. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0029-6.

Moore SC, Lee IM, Weiderpass E, Campbell PT, Sampson JN, Kitahara CM, et al. Association of leisure-time physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jun 1;176(6):816-25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548.

Rock CL, Thomson C, Gansler T, Gapstur SM, McCullough ML, Patel AV, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Jul;70(4):245-271. doi: 10.3322/caac.21591.

Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018 Nov 20;320(19):2020-2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854.

Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Lynch BM. State of the epidemiological evidence on physical activity and cancer prevention. Eur J Cancer. 2010 Sep;46(14):2593-604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.028.

Kerr J, Anderson C, Lippman SM. Physical activity, sedentary behaviour, diet, and cancer: an update and emerging new evidence. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Aug;18(8):e457-e471. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30411-4.

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Dec;54(24):1451-1462. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955.

Shailendra P, Baldock KL, Li LSK, Bennie JA, Boyle T. Resistance training and mortality risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2022 Aug;63(2):277-285. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.03.020.

Modi HD, Byrne S, Li LSK, Boyle T. Resistance training and the risk of breast cancer: a population-based case-control study. J Phys Act Health. 2025 Jan 17;22(4):479-484. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2024-0327.

Thank you Sara for collaborating on this article! If anyone has specific questions about exercise oncology, feel free to post here or reach out!

Thank you for this!! I have been walking briskly for about 20 to 30 minutes 3 to 4 times a week,but when I miss days I feel bad, but now I know that thats better than nothing! And I'm definitely going to aim for more days and try to get in some strength training.